The Vesey Republic

Black Nationalist - Fanonist - Womanist

Mireille Fanon

Frantz Fanon

NewBlackNationalism.com

"It was through my initiative that Sartre’s preface to The Wretched of the Earth was removed. Let us say that from a western point of view, it is a good preface. Sartre understood the subject matter in The Wretched of the Earth.

But in June 1967, when Israel declared war on the Arab countries, there was a great pro-Zionist movement in favor of Israel among western (French) intellectuals. Sartre took part in this movement. He signed petitions favoring Israel. I felt that his pro-Zionist attitudes were incompatible with Fanon’s work.

Whatever Sartre’s contribution may have been in the past, the fact that he did not understand the Palestinian problem reversed his past political positions."

Josie Fanon, 1978 - Howard University

Marie-Josephe Duble "Josie" Fanon - Intellectual,

Journalist, and Liberation Fighter 1931 - 1989

Marie-Josephe Duble, called 'Josie,' was born in 1931 in the Lyon region of France. The eighteen-year of Corsican-gypsy descent first met the 23 year-old Frantz Fanon in Lyon in 1949.

She was a liberal arts lycee student, while Fanon was studying to earn his degree in psychiatry at the University of Lyon. Her parents, both postal workers, and open leftist trade union activists supported the marriage.

Josie met Fanon under difficult circumstances. A previous relationship Fanon had with a medical student in Lyon ended in 1948 in a pregnancy. Fanon's refused to marry Michelle B., who bore his first child, Mireille.

In conservative Lyon, pre-marital sex was taboo, as were interracial marriages. Abortions were illegal. After being persuaded by friends and family, Fanon recognized Mireille as his issue. Ironically, Michelle B. married a psychiatrist: Marielle, took his last name and lived up to its radical credentials.

Josie recalled that the early Fanon "had assimilated all the cultural values of France. This pathology," she said, "is common to the people of the French-speaking Antilles. Even today, these colonies are the territories where French colonialism has been the most over-emphasized, most perfidious, and most noxious."

After finishing his studies in Lyon, Fanon took a residency at Saint-Alban-sur-Limagnole in 1951, under the radical Catalan psychiatrist François Tosquelles. From their small apartment there, Fanon paced back and forth, unleashing rapid fire staccato bursts of free associative thinking in what became his first major work, Black Skin, White Masks. It was Josie, that performed the daunting task of taking dictation for Fanon--who didn't type--and crafted his words into a manuscript.

Black Skin, White Masks was published in 1952, the same year the couple were married. A keen mind in her own right, Josie successfully sat for her examination at the University of Lyon in 1953 in Latin philology--the study of language in oral and written historical sources. After Fanon's second residency at Pontorson, near Mont Saint-Michel, he was ready for a permanent clinical posting.

Fanon looked for work in Martinique, Guadeloupe, and Senegal. Finding none, Fanon took the job at the psychiatric in Algeria as chef de service at the Blida-Joinville Psychiatric Hospital. Arriving in Algeria in 1953, Fanon threw himself into his psychiatric work with slightly over 200 patients.

Throngs of students from Algeria came to Blida-Joinville to observe the clinic's work and learn from Fanon's unorthodox case studies. Often preoccupied with his patients, Josie was their gracious host. In 1955, she gave birth to their son Olivier.

After deciding to join the Algeria's National Liberation Front, Fanon could no longer safely maintain his position in Blida-Joinville. The Fanon's moved to Tunisia capitol city of Tunis. Fanon assumed a full time position as an editor of the FLN's flagship newspaper, Moudjahid.

At the same time, Josie began writing articles without attribution for the Tunisian radical journal, 'El Action.' With Fanon increasingly coming in the crosshairs of the French intelligence services, Franz and Josie living a semi-clandestine lifestyle. She took the name of "Nadia."

In 1961, Fanon was diagnosed with leukemia. Again, it was Josie by his side taking dictation of his last revolutionary testament to the Third World and his "New Humanist" project, The Wretched of the Earth.

In October of 1961, unable to get treatment at a hospital in Rome or Paris, because of security concerns, Fanon reluctantly agree to seek treatment in the United States. Fanon Josie and young Olivier came to the United States to be with him in his final days. They were housed as guest at the Guinean Embassy. Fanon entered Bethesda Naval Hospital in Bethesda, Maryland in late October.

Fanon's blood was changed completely in the hopes stimulating the production of bone marrow, but to no avail. During his stay at Bethesda Naval Hospital, Fanon was visited by NLF's New York Delegation, African diplomatic corps in Washington, D.C., and his brothers. On the morning of December 6, 1961, Josie received Fanon's last words. "They put me through the washing machine last night." s

Fanon died three days after Wretched of the Earth was published. The book was banned and seized by the French government from bookstores and burned. Fanon's body was returned to Tunis, and then transferred inside of liberated Algeria, where he was committed to rest for the ages.

No sooner had Josie returned to Algiers, the FLN revolutionary movement came to power one year later. Josie shared Fanon's love and dedication to the independence movement in Algeria. She would comment that;

"It is always difficult to say what an individual like Fanon would have done if he had not died when he did. In his life, two things interchanged constantly. He would certainly have maintained his political activities. However, I cannot say with certainty where. No doubt, he would have stayed in Algeria — at least for a while. He had fought for its independence and because Algeria was a country very dear to him.

From 1962 until 1977, she worked for the Algerian press and the Front for National Liberation. After 1977. Later, Josie wrote for the Pan African magazine, Demain L'afrique [Tomorrow Africa], a monthly publication.

The guardian of Fanon's work, Josie successfully lobbied the publishers of Wretched of the Earth to remove Jean Paul Sartre's preface to the book after he signed a petition supporting Israel's pro-Zionist attitudes. Josie said, and correctly so, that Sartre's pro-Zionist position was incompatible with Fanon's work.

By the late 1980's, the vicissitudes of life had began to wear on Josie who was approaching her sixtieth birthday. A wave of student protests broke out in Algiers. Assia Djebar was a close friend who spent a great deal of time in late 1988 and 1989 with Josie. In the following passage she describes the tragedy that marked Josie's last year.

"The first days of October 1988, Algiers reached a fevered pitch; under Josie's balcony in El-Biar, adolescents in revolt were the first to set fire to police cars.

"The next day and the following days, this time in the heart of Algiers, the army swarmed the capital, and, confronted with peaceful demonstrations, opened fire: six hundred young people were shot down.

From one end of the rioting town to the other, not being able to meet, we would speak on the phone: I still hear today Josie's enraged voice commenting endlessly on the scenes that she'd observed or that people had told her about.

Once more, O Frantz, the 'wretched of the earth!

Josie and her big gypsy eyes.... And above all her voice, that happy contralto. For she would laugh--she loved to laugh!... How will I ever learn to grow old, now that Josie Fanon, my elder, cannot show me the way with her laughter and her brazen humor?

In June, she had made the trip to the Tunisian border to visit Frantz's grave. (I am sure that it was then she made her decision: to join him.)

In Tunis, she returned to every place they had lived. Back in El-Biar, she took several days to put all her things in order: photographs, poems she was writing, Frantz's letters which she had compiled and arranged much earlier, letters of her son, her friends.

She gave her young neighbor, Karim, various presents, 'to remember me by' she told him gently when he'd protest or try to refuse, his heart fearful.

She made sure the cleaning woman was even more meticulous. She would linger, I feel it, every morning to listen to the sounds of neighboring families rising from the courtyard: I see her low bedroom, filled with multi-colored rugs where we would stay, the window open as if above a well, to catch the rising noises, women's laughter, whining children.

I hear Josie letting herself be wrapped in these sounds of Algerian life, by this everyday profusion.

But she has decided: since her visit to Frantz's grave; she is determined.

She phones her son in Paris to reassure him: yes, she will start therapy again with the family psychologist. Yes, he wants to hospitalize her for a week or two, no more. Her son should put his mind at rest, she will do it. No, she does not feel alone: he should not be worried; there's no need whatsoever for him to come.

And so she willingly went to the hospital. On the condition, she told the doctor, that they let her go home to her apartment on the weekend: be with her flowers, the sound of the neighbors, the concern of Karim and his mother.

She rested in the hospital for six days. She brought books, music. She read; even more she daydreamed, looking at the summer light from her bed. Hardly spoke.

'She was smiling at us when she left,' a nurse recalled, unable to forget the gentleness in Josie's large eyes, her voice so near.

Josie went home to El-Biar on Thursday evening.

'I'll be there Friday!' she declared.

The nurse waited for her on Sunday. Very early on the previous day, by the light of dawn, Josie opened the window of her living room that looked out onto the street. pulled a chair over. Took off her shoes. In one or two seconds, glanced around the rooms in which everything was in its place. A last glance at the geraniums on the neighboring balcony.

With her back finally turned on her home and her life, Josie Fanon threw herself out of her fifth-story window. The 13th of July, 1989; El-Biar, above Algiers. A Friday. In her fall, Josie hurt no one: only she exploded."

Josie Fanon spent her last days watching an unjust, dictatorial Algerian government shooting and beating its youth beneath her balcony in Algiers.

The warnings her husband so presciently forecasted--the words she hammered out her typewriter--on his deathbed in Wretched of the Earth about the pitfalls of a national bourgeoisie and Islamic ideologues imposing a new tyranny on the masses unfolded on her front doorstep.

The reversal of the nationalist revolution Josie and Fanon gave their lives for conjures visions of an ironic and profound tragedy. It's not. We are their successors. Just as Fanon's daughter, Mireille, whom he never had a relationship with continues to carry on the struggle, and the family name, so must we.

We cherish and remember the life, work, and spirit of Josie Fanon.

Josie Fanon Interviews Che Guevara

Josie Fanon: Would you indicate in broad outline the position of the Cuban government in relation to Africa as a whole?

Che Guevara: Africa represents one of the most important, if not the most important, fields of battle against all the forms of exploitation existing in the world, against imperialism, colonialism, and neocolonialism. There are big possibilities for success in Africa, but there are also many dangers.

Interview with Christian Filostradt

"When I met Frantz, he had been already in France about four years. Understand that he was from Martinique; born in a French colony, he had assimilated all the cultural values of France. This pathology is common to the people of the French-speaking Antilles. Even today, these colonies are the territories where French colonialism has been the most over-emphasized, most perfidious, and most noxious."

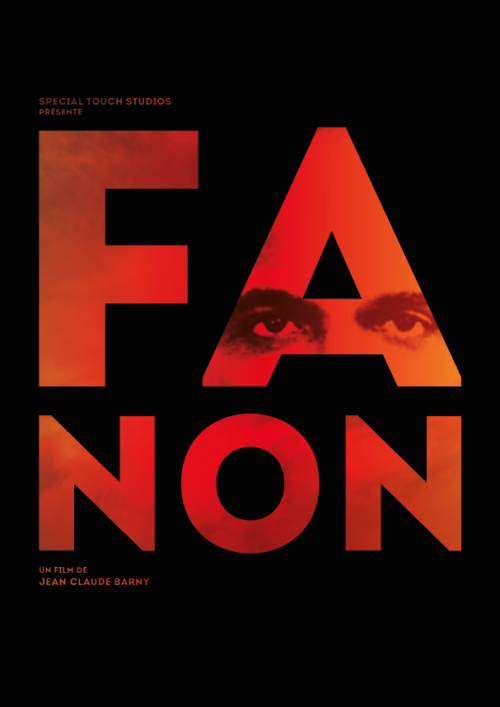

The Movie: Coming in 2024

Josie Fanon will be played by Belgian actress Déborah François

Akoroko — African Cinema Now!

@akorokoafrica

Jean-Claude Barny's Frantz Fanon film, FANON, has cast its lead: relative newcomer Alexandre Bouyer. The project recently received a $1.4M award from Film Fund Luxemburg. "We are convinced that his interpretation of Frantz Fanon will be as captivating as it is inspiring."

Josie Fanon, Fanon's wife, will be played by Belgian actress Déborah François. The rest of the cast includes Stanislas Merhar, Mehdi Senoussi, Olivier Gourmet, Arthur Dupont, Salomé Partouche, Nicolas Buchoux, Salem Kali, and Sfaya M'Barki.

This is director Barny's 3rd film.

The Fanon Arguments